One of the most important if least visible consequences of expanding oil and gas production in the Permian Basin is the growth of the petrochemical and plastics industry. Petrochemicals and the plastics they make pose dangerous threats to communities and the environment all along the supply chain — from the well-head to the warehouse.

Petrochemicals are chemicals derived from oil and gas that are not burned as fuel but are used to make plastics, fertilizers, adhesives, and other products. Some petrochemical-based products, especially fertilizers, are made from methane (‘natural’ fossil gas). Gas liquids, however, are by-products of oil production and are increasingly used to produce petrochemicals. Gas liquids, such as ethane, propane, and butane, represent a significant and growing portion of the hydrocarbons produced globally, a trend that is especially true in the Permian Basin.

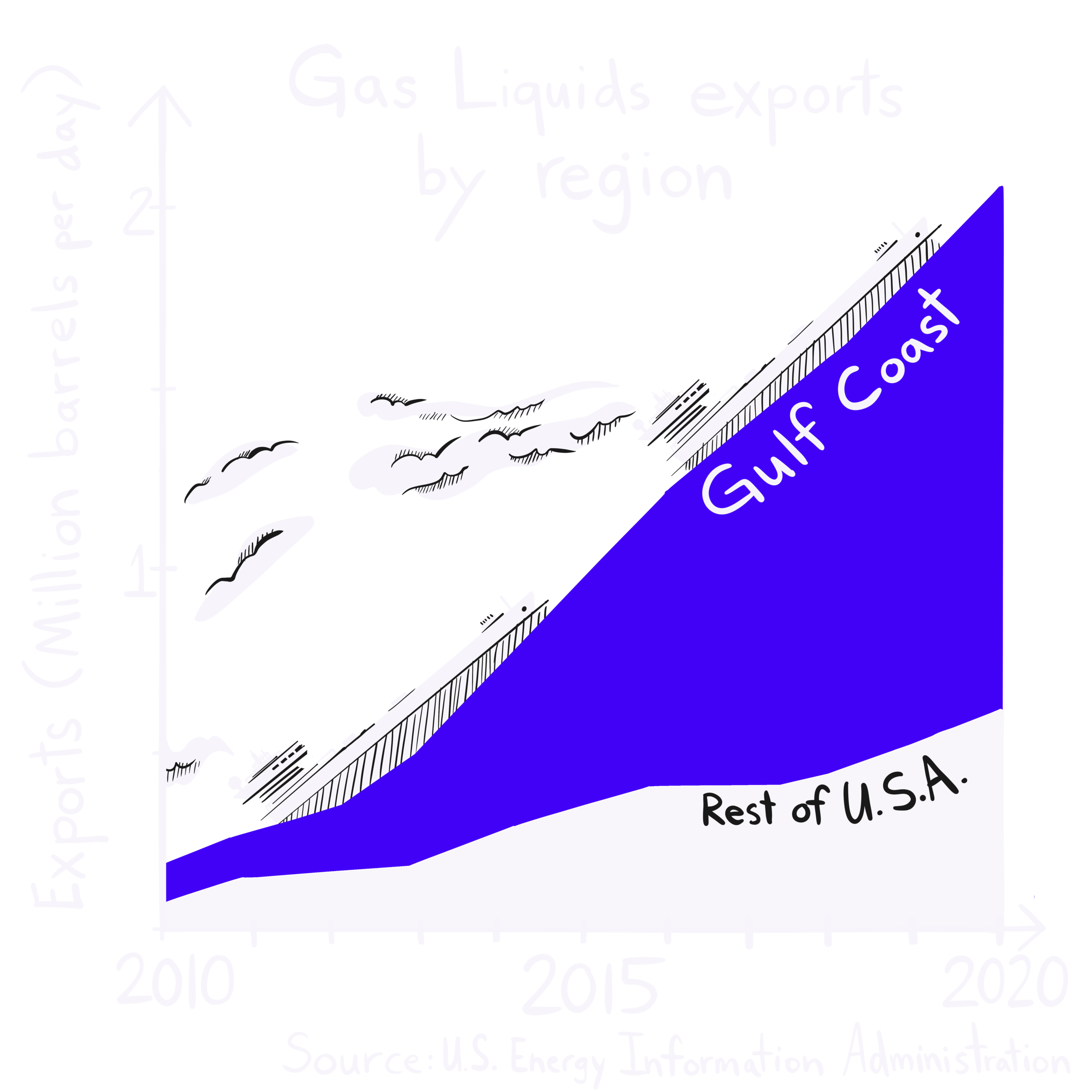

The oil and gas industry expects plastic to drive oil demand growth over the next several decades and expects the Permian to be a significant source of gas liquids for use as feedstock. At 617 million barrels (bbl), the Permian Basin produced more gas liquids in 2020 than any other country or basin in the world. Permian gas liquids production far surpasses all other producers, including Canada, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates.

If this trend continues, business-as-usual gas liquids production in the Permian is expected to increase to 880 million bbl per year by 2030. The increased availability of gas liquids, especially ethane, has driven a massive wave of investment in new facilities to put these chemicals to use, particularly to make plastics and their petrochemical building blocks. In addition to the climate damage and local harm fracking causes, the expansion of petrochemicals and plastics production endangers even more communities.

Petrochemical and plastic production facilities have a multitude of impacts, including:

Polluting the communities where they operate, through air emissions and water contamination;

Exacerbating the climate crisis due to high emissions from their energy- and pollution-intensive processes;

Contributing to the ongoing health and environmental crisis of plastics pollution;

Helping to justify and perpetuate fracking and fossil fuel production in a world moving to phase out the use of oil and gas for transportation and energy supply.

The plastic on the shelf comes from a fracking well

Plastic is fossil fuel in another form. Fracking wells are typically categorized by their primary product — either liquid oil or gaseous methane. However, both oil and gas wells produce light hydrocarbons such as ethane, propane, and butane, which are also used in various applications beyond combustion for heat or energy. The most significant of these applications is the production of plastic.

The process to turn gas liquids into plastic requires many steps and is extremely energy-intensive. First, gas liquids must be separated from the rest of the dry gas stream, then distilled into their component molecules in a process called fractionation. These chemicals must then be “cracked,” a process that chemically alters each molecule under conditions of extreme heat and pressure. Once cracked, these monomer molecules are strung together into very long chains called polymers. Depending on the type of plastic being made, these polymers are often mixed with additives that are themselves derived from fossil fuels, require significant energy to produce, and are toxic to humans and animals. Such additives include plasticizers, dyes, flame retardants, and more, which are integral to the production of various forms of plastics.

Plastics and petrochemicals are a dirty business

Plastic presents a profound threat to human health throughout its lifecycle, and the push to increase plastic production will only heighten the risks and worsen the impacts. In addition to the severe impacts of fracking on water, air, soil, and ultimately human health, the chemical refining processes to make petrochemicals and plastic release large quantities of hazardous chemicals. These include persistent organic pollutants (POPs), endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), and carcinogens.

Many of the companies driving the petrochemical expansion are the same companies fracking in the Permian Basin. ExxonMobil and ChevronPhillips (a joint venture of Chevron and Phillips Petroleum) are just two of the several companies building petrochemical facilities on the Gulf Coast. Other multinational corporations, including Dow, subsidiaries of the Formosa Plastics Group, and the Saudi Basic Industries Corporation (SABIC), are investing in new petrochemical production capacity as well.

Climate Change and Petrochemicals: Risk Upon Risk

No matter their location or which company operates them, petrochemical facilities pose a threat to surrounding populations. Even when they have emergency preparedness plans, chemical facilities are inherently dangerous, especially in the face of extreme weather events, which can trigger accidents such as chemical spills, fires, and explosions at industrial sites. Such incidents not only threaten the environment and the health of workers and surrounding communities, but can also damage local economic activity and recreation as well.

Climate-fueled storms are heightening these risks. In the last few years, the Atlantic has had above-average hurricane seasons. In 2019, five tropical cyclones formed in the Gulf of Mexico, tying the records from 2003 and 1957. Twenty tropical cyclones made landfall in the United States in 2020, breaking a record set in 1916. 2021 has been no exception to this trend. Hurricane Ida is a prime example. Following the storm, state and federal regulators reported more than 2,000 oil and chemical spills into Louisiana's waters and lands, with unknown long-term consequences for local environments and communities.

Finally, the petrochemical industry is not just at risk from climate change, it is also a growing driver of climate change. The production of fossil fuels and the petrochemicals and plastics derived from it is enormously energy- and emissions-intensive. Greenhouse gases are also emitted in the management of plastic waste, especially when that waste is incinerated. Finally, emerging research suggests that once in the environment, degrading plastic may release methane in a process known as ‘off-gassing.’ Microplastics, tiny plastic particles that are found in nearly every corner of the planet including the oceans, may interfere with plankton which sequesters carbon from the surface oceans — further contributing to the accumulation of greenhouse gases and disrupting the biological carbon cycle. Increasing petrochemical and plastic production with NGLs from the Permian is at odds with a pathway that limits global warming to 1.5°C above pre-Industrial levels.

The petrochemical industry exacerbates environmental injustice

New and expanded petrochemical production facilities threaten public health and exacerbate existing environmental injustices. Petrochemical facilities tend to be geographically clustered due to the physical nature of the feedstocks and the cost of transportation. This clustering, and the siting decisions that led to it, has concentrated the toxic burden of Permian plastic production in predominantly Black communities and other communities of color.

There are two major petrochemical clusters in the United States: the greater Houston area along the Texas Gulf Coast and an 85 mile-long industrial corridor along the Mississippi River in Louisiana commonly known as ‘Cancer Alley.’ Both of these petrochemical hubs are fed by oil and gas from the Permian Basin, and are the primary regions where new plastics and petrochemical processing and production facilities are sited or are currently under construction.

Houston, Texas

The community of Manchester/Harrisburg, Texas, part of the city of Houston, is home to the largest petrochemical complex in the United States, and one of the largest in the world. Ninety percent of residents in Manchester/Harrisburg live within one mile of a chemical facility. The concentration of toxic emissions in the area has caused significant health concerns among the residents, who are mostly people of color.

St. James Parish, Louisiana

Louisiana’s Cancer Alley contains seven out of the ten census tracts with the highest cancer rates in the United States. There are nearly 100 petrochemical facilities in the region. St. James Parish is just one of the many affected communities. Despite the enormous health and environmental threats posed by the petrochemical industry, the Taiwanese company Formosa Plastics Group has plans to build a 2,400 acre complex dubbed the ‘Sunshine Project’ in St. James Parish. The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) has issued the company a permit for the project authorizing it to double the level of toxic air emissions in the surrounding community, exacerbating residents’ exposure to chemicals used in the plastics and petrochemicals manufacturing process. Many of those chemicals cause cancer, respiratory disease, and other health problems, and thus increased exposure is likely to compound the ongoing health impacts of decades of environmental racism from other nearby facilities. Parish zoning changes adopted in the mid-2010s have helped steer Formosa Plastics and other new plants into small and predominantly poor Black communities like western St. James Parish. However, residents are fighting back and their campaign to Stop Formosa has gained national and international support.

Beyond Houston and Cancer Alley

The impacts of the petrochemical supply chain are not restricted to these two clusters, however. Along the way, from the fracking well to the cracker plant are pipelines, compressors, and highly-polluting gas processing plants. In particular, communities in the Midland/Odessa area of the Permian Basin, the location of many gas processing plants, have long been plagued by poor air quality, due in large part to the pollution from those facilities. This air pollution is known to have serious environmental and public health consequences, such as lung damage, asthma, and heart attacks.

Take Action

You Can Help Defuse the Permian Climate Bomb.

Sign up to learn more about the role you can play in ending this crisis & get updates when future parts of this series are released.